There had been 103 German air raids on Britain in World War 1 using Zeppelin airships and Gotha heavy bombers. ‘The First Blitz‘ killed 1,000 people in London alone. This memory loomed large in the minds of politicians and others as a second World War appeared increasingly likely.

In November 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain placed Sir John Anderson in charge of Air Raid Precautions. Sir John was a scientist turned politician who led the Ministry of Home Security whose responsibilities covered all central and regional civil defence organisations, such as air raid wardens, rescue squads, fire services, and the Women’s Voluntary Service. It was also responsible for providing public shelters.

Anderson commissioned the engineer William Patterson to design a small and cheap shelter that could be erected in people’s gardens. The first ‘Anderson’ shelter was erected in a garden in Islington, London on 25 February 1939 and, between then and the outbreak of the war in September, around 1.5 million shelters were distributed to people living in areas expected to be bombed by the Luftwaffe. During the war a further 2.1 million were erected, making a total of 3.5 million.

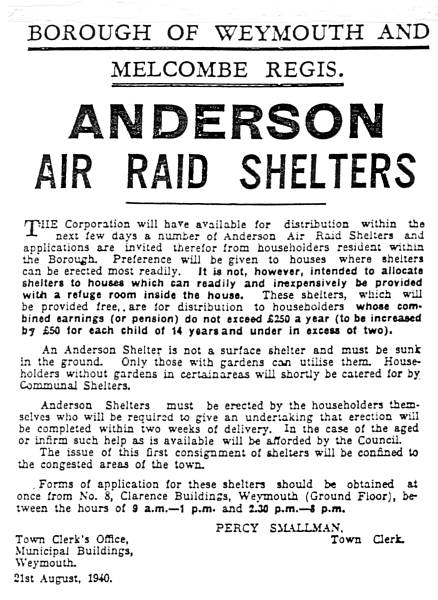

Anderson shelters were issued free to all householders who earned less than £250 a year, and those with higher incomes were charged £7 (The equivalent figures would be around £21,000 and £600 in 2025).

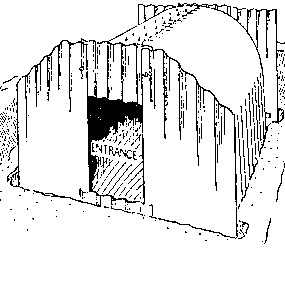

Typically made from six curved sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end, and measuring 1.95m by 1.35m, the shelter could accommodate four adults and two children. The shelters were normally half buried in the ground with earth heaped on top. (See below for indoor use)

But there were shorter and longer shelters. Professor Ray Cole of the University of British Columbia kindly sent me a a document which summarised the numbers of shelters distributed to date as 507,688 4 person (i.e. 4 sheets of metal), 1,845,275 6 person, 99,881 8 person and 32,034 10 person – a total of 2,484,878. There were 1,174,751 ‘standard’Table Type’ Morrison shelters issued in the same period, plus 9,350 ‘Two-Tier Type.

It wasn’t too difficult for individual householders to build the shelters themselves, or maybe neighbours would help each other. Alternatively, Robert Hutton reports (in his non-fiction book Agent Jack) that ‘Audrey and the children would have to trust themselves to the Anderson shelter that [bank clerk] Eric, never a handyman, had paid some builders to put up in the back garden’.

I understand – though I haven’t seen the detail – that the shelters were issued free of charge to all householders later in the war. Before that, householders who had been issued with free shelters (and who didn’t have big families) sometimes allowed their slightly better off neighbours to share them.

The shelters were very strong – especially against a compressive force such as from a nearby bomb – because of their corrugation. Click here for further information about their strength and durability. And their construction instructions are here.

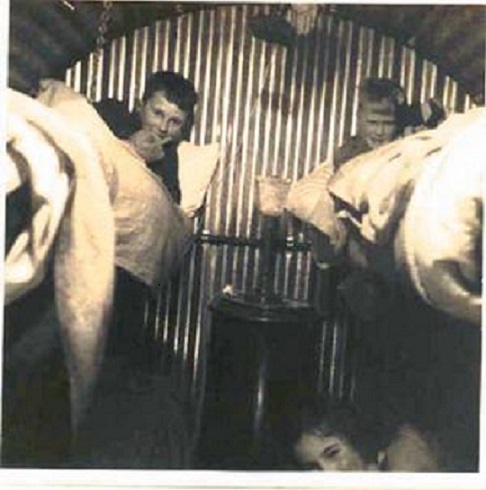

Anderson shelters were effective only if half buried in the ground and covered in a thick layer of earth. They were therefore inherently cold, dark and damp. In low-lying areas the shelters tended to flood, and sleeping was difficult as the shelters did not keep out the sound of the bombings. Families had to build their own bunk beds, or buy them ready made. If there was a toilet at all, it took the form of a bucket in the corner. Therefore, although some families slept in them every night, most people were reluctant to use them except after the air raid sirens had sounded – and often not even then.

Some families chose to move their shelters indoors. The Home Office issued advice on how to do this, and so create ‘an anti-debris shelter indoors’, in August 1942

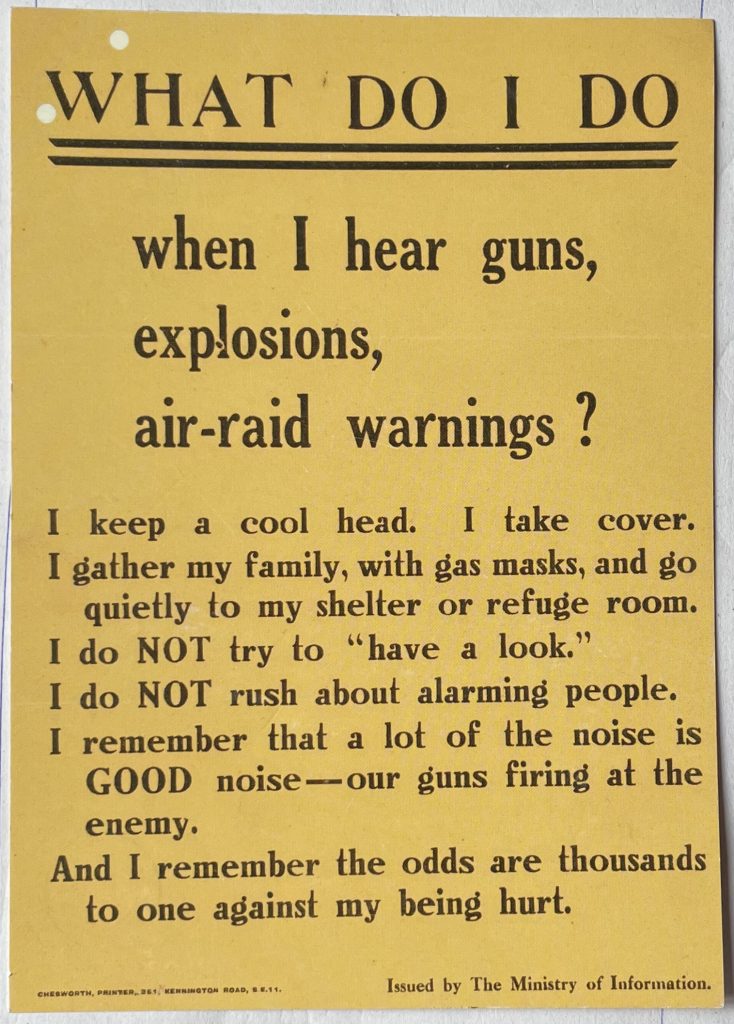

People were recommended to take important documents with them, such as birth and marriage certificates and Post Office Savings books. But it was difficult to remember what to do when you had just woken from a deep sleep, it was totally dark and the sirens were wailing.

Another problem was that the majority of people living in industrial areas did not have gardens where they could erect their shelters. It is therefore not surprising that a November 1940 survey discovered that only 27% of Londoners used Anderson shelters, 9% slept in public shelters and 4% used underground railway stations. The rest of those interviewed were either on duty at night or slept in their own homes. The latter group felt that, if they were going to die, they would rather die in comfort.

Many families tried to brighten their shelters in various ways, and they often grew flowers and vegetables on the roof. One person wrote that “There is more danger of being hit by a vegetable marrow falling off the roof … than of being hit by a bomb!’

But others were more nervous – and with good cause. After a parachute bomb hit a nearby school, one set of Bournemouth parents – the Heaths – decided to erect their shelter indoors, and cover it with sandbags.

So the Heath’s shelter is a good example of an Anderson shelter which was adapted for indoor use – although Morrison shelters were more often used for this purpose as they were specifically designed for indoor use. Further information about the indoor use of Anderson shelters may be found in the National Archives (HO 197/23 and 205/9 and London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/CD/3/89)

After the war

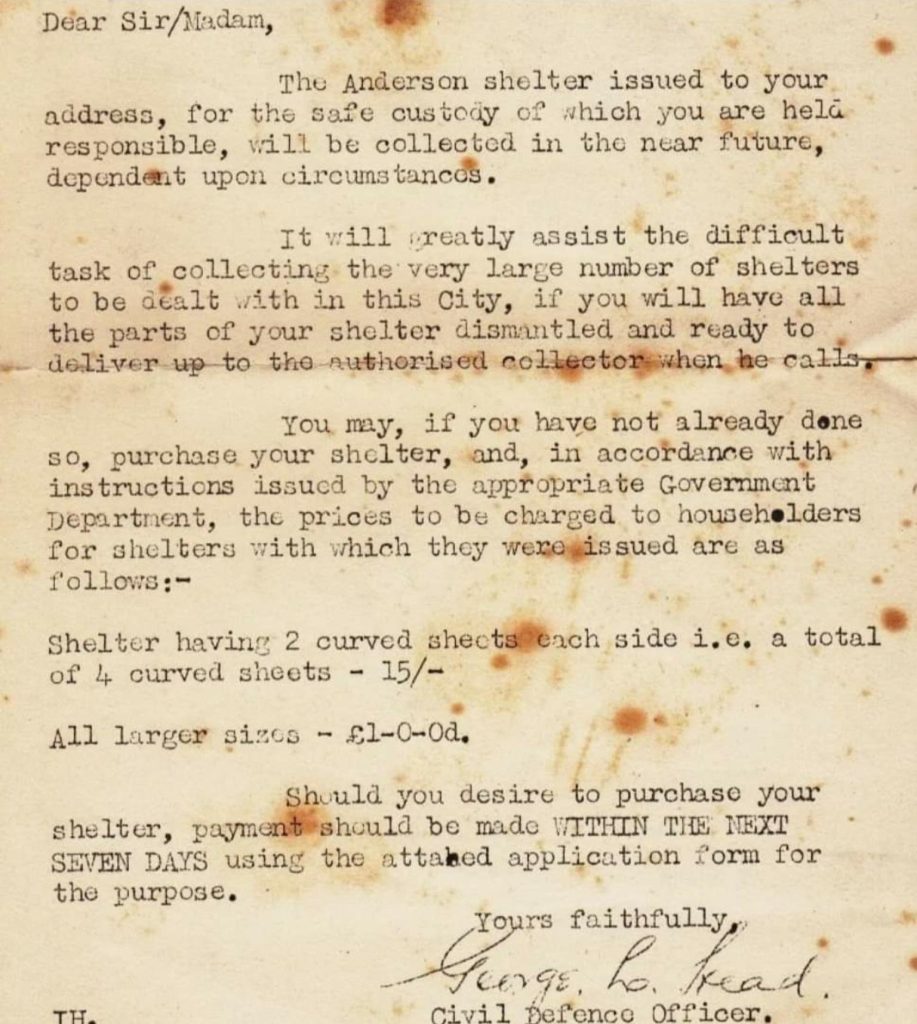

The corrugated iron roofs of most of the shelters were collected by the authorities at the end of the war.

Others were sold to the householders for either 15 shillings or £1, depending on the size.

People who bought their shelters often dug them up and re-erected them above ground, fitted them with proper wooden doors, and used them as workshops or garden sheds.

John Summers & Sons

This steel making company had a large steel mill at Shotton in North Wales. Its official history records that:

Even before the official declaration of hostilities, the works had moved into the production of galvanised sheets for Anderson garden air raid shelters, producing them at the rate of 50,000 a week. Prototypes were tested in the General Office area where aerial bombs weighing 500lb were detonated within 25 feet of a group of shelters and 75 tons of pig iron was piled on a shelter roof. One brave volunteer went into a shelter while a heavy concrete ball, normally used for breaking up slag, was dropped on it! The shelter was virtually undamaged and the volunteer survived to tell the tale.

The Anderson air raid shelter, made of curved corrugated steel sheet, saved many lives during the Blitz of the major cities. Designed by the British Steelworks Association in early 1939, the structure was 6ft.6 in. long, 6 ft. high and 4 ft. 6 in. wide and was made of 14 gauge galvanised steel sheet. It was sunk into the ground to a depth of three feet.

The company even designed its own shelters, improving on the standard Anderson design by manufacturing semi-circular sheets which did not need to be bolted at the top, and so could be constructed more easily.

Notes

“Despite Hitler’s orders that he alone was to decide on terror bombing, 100 planes of the Luftwaffe, acting, it seems, under a loosely worded directive from Göring … had attacked London’s East End on the night of 24 August 1940. As retaliation, the RAF carried out the first British bombing raids on Berlin the following night. Hitler regarded the bombing of Berlin as a disgrace. … his reaction was to threaten massive retaliation. … From 7 September the nightly bombing of London began.”

Ian Kershaw ‘Hitler’ p570.

German strategic bombing of the UK between 1939 and 1945 killed around 50,000 people. London, Liverpool and Birmingham were the most bombed cities, in that order. Here, above, is a 1945 view of the area around St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Similar attacks on German cities killed around 500,000 – ten times as many. Many of the later attacks were carried out by Britain’s Bomber Command which itself lost 50,000 crew in the conflict. The single atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima killed between 90,000 and 140,000 Japanese.

The V2 rocket bomb killed around 2,700 in England and destroyed around 20,000 houses, damaging another 580,000 through their enormous shock-waves.

In total, during the war, around 220,000 UK dwellings were destroyed or so badly damaged that they had to be demolished. At least 3.5 million more suffered some form of damage. Around 30% of the country’s pre-war housing stock was affected in some way.

For every civilian killed, 35 were forced out of their homes by the blitz.

There is now a strong body of opinion which believes that it was a mistake for the Government to provide Anderson shelters rather than building deep bomb-proof public shelters of the sort promoted by Ramon Perera, who had overseen the building of a large number of such shelters in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). British engineer Cyril Helsby helped Perera escape to Britain as Barcelona fell to Franco’s troops in 1939, but neither could persuade the British establishment to invest in more substantial shelters which would have saved many lives.

It is possible that Ministers thought that factory, transport and other workers might opt to stay in truly safe shelters rather than return to work after bombs had stopped falling, even though there was no evidence that this had happened in Barcelona. The full story was told in a TV de Catalunya “30 Minuts” documentary, produced in collaboration with Justin Webster Productions and first shown on Spanish TV in 2006.

Reports about the ‘Blitz Spirit’ and all that need to be received cautiously. History is, after all, written by victors and survivors. People weren’t ‘heroic’. They had no choice but to do their best to survive in a terrible time. Some felt abandoned by the government, and some Londoners insisted on staying in Tube stations even though this was expressly forbidden at first. Others moaned about the blackout and other restrictions which led to increased deaths caused by falls and road accidents.

For more information I recommend Richard Overy’s article The Dangers of the Blitz Spirit.

And Kenley (Airfield) Revival have lots of interesting information including lots of interesting Air Raid Precautions (ARP) documents.

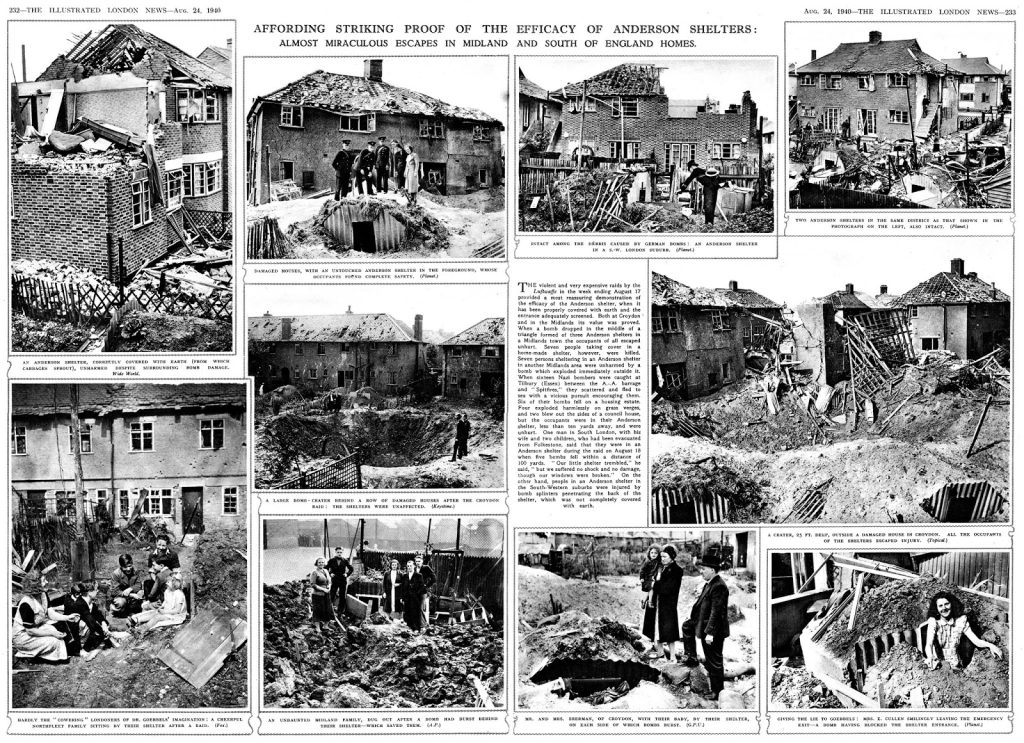

Here, finally, is an interesting double page spread from the Illustrated London News of 24 August 1940.